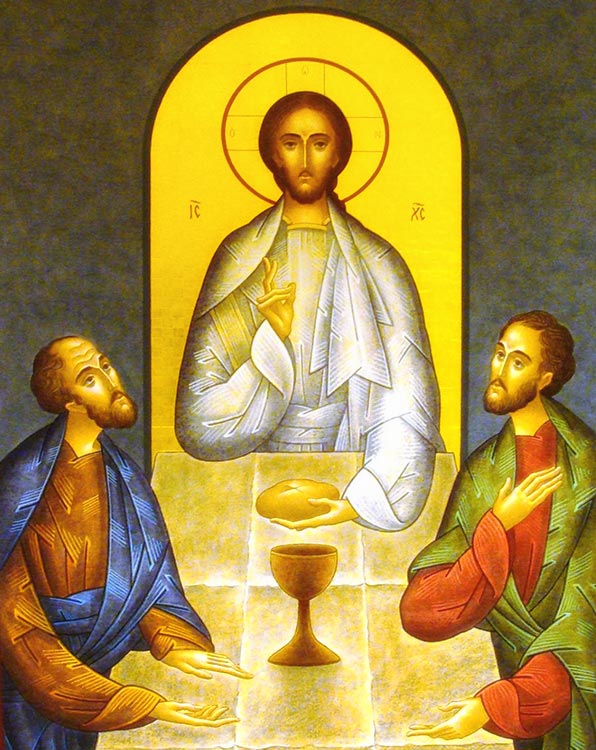

Once the creed is completed, a little dialogue between the leader of the Liturgy and the people leads us into the central portion of the rite, the heart and soul of the Liturgy, expressed in the anaphora, i.e. “the offering,” the “lifting up.” To repeat, each major part of the Divine Liturgy is marked by what is often seen as a blessing but which is really a greeting, a welcoming to a deeper (perhaps more accurately, a higher) level of the mystery. The earliest record we have of a rudimentary anaphora (even older than the Gospel accounts) is found in St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians (11:23 & ff.) He begins by saying, “I received from the Lord what I handed on to you. On the night before the Lord Jesus was betrayed, he took bread—and giving thanks—he broke it and said, ‘This is my body for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ Likewise, he took cup after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.’ For as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the death of the Lord until he comes.’” From these words, so simple and yet so majestic, all the formulas for the Eucharistic Prayer evolved and developed.

As Justin tells us, originally the leader of the Eucharist improvised the anaphora, “to the best of his ability.” In time, some of these anaphoras were recorded and circulated. In the third Christian century the standardizing of the Eucharistic prayer began, but even at that date the local bishop had a great deal of flexibility with the text.

Today there are two texts for the Divine Liturgy ordinarily used in the Ukrainian Church, and permission for a third if desired. The first is the text of Saint Basil the Great, originally the ordinary text for all Sundays of the year and now relegated only to the Sundays in Great Lent and the vigils of certain feasts, like Christmas and Easter, and a few other days. Evidence shows it began to develop before St. Basil’s time in the region of Caesarea in Cappadocia where he would become archbishop. At the end of the sixth century, Leontius of Byzantium refers to the Liturgy of Saint Basil and says the saint “wrote it down under the influence of the Holy Spirit.” By the seventh century many more texts were attributing it to Saint Basil; and by the eighth century, all of them. It is certain that Basil did not write the whole text of what we call today the Liturgy of St. Basil, but utilized some existing text, possibly the Liturgy recorded in the Apostolic Constitutions (Antioch), or the Liturgy of St. James (Jerusalem), and edited it. In a document credited to Patriarch Proclus of Constantinople, the author says, “St. Basil, aware of the laxity and weakness of human beings who find the Liturgy a burden because of its length, gave permission to use a shortened version.” But Basil did not simply shorten the text, it is clear he also added new material, especially with regard to the Holy Spirit, of whom he was a champion in a time when many were denying that the Spirit was of the same substance as the Father and the Son, and equal to them. This helps to explain what many Westerners see as a “double consecration” of the Bread and Wine. After repeating the words of the Lord Jesus—and even inserting the words “sanctified it” into the text as recorded in the Gospels—Basil moves on to what we call the epiclesis (Greek ἐπίκλησις, meaning “a calling down,” an “invocation upon.”) In Basil’s Liturgy God the Father is asked to “show (reveal) this bread to be the Body of your Christ, and that which is in this cup the Blood of your Christ, changing them by your Holy Spirit.” In the Liturgy of Chrysostom the text is slightly different, “make this Bread the Body of your Christ, and that which is in this cup the Blood of your Christ, changing them by the Holy Spirit.” This is one good example of how changes in liturgical rites are made to address important issues of faith and theology.

“Not long after that, our Father John Chrysostom . . . wanted to completely eradicate this diabolical excuse (“It’s too long!”), so he removed even more from the rite and ordered it celebrated in an even shorter form.” It would take longer for what we call the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom to be credited to him, and not before the eighth century. In this case, a West Syrian anaphora of the Twelve Apostles, probably the usual Liturgy at Antioch, seems to be the text that Chrysostom was using, and the edited version would became the usual Liturgy of Hagia Sophia, the cathedral in Constantinople where Chrysostom was archbishop from 398 to 404. From there it spread to the whole Byzantine Empire. And while the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom is shorter than that of St. Basil, it incorporates a different theological emphasis: it expanded the commemorations (anamnesis) that followed, as well as the epiclesis, showing a new appreciation for the symbols that mediate the experience. From the imperial capital it spread to the whole Byzantine world, relegating St. Basil’s text to a subordinate position.

The oldest of Eastern Liturgies is that of St. James, called the Brother of the Lord and first bishop of Jerusalem. It is so old—and has been redacted and adjusted so often by so many—that it is close to impossible to visualize precisely what it was like at its inception. But even today, in whatever edition it exists, it is possible to see a more Semitic spirituality, centered on some of the imagery found in the Letter to the Hebrews in the Bible. It appears that some of the Liturgy of St. James was incorporated into the Liturgies of both St. Basil and St. John Chrysostom. This Liturgy is still used on a few days in various places, Catholic and Orthodox, and Bishop Robert Moskal gave permission for its use in the Eparchy of St. Josaphat, even recommending various texts for use.